PORT ANGELES — A deadly liver disease is being ignored despite its growing prevalence, a state epidemiologist told the Clallam County Board of Health last week.

Hepatitis C is on the rise on the North Olympic Peninsula and other regions across the country, said Dr. Scott Lindquist, state epidemiologist for communicable diseases with the state Department of Health.

“I don’t know of any other infectious disease that we ignore so completely as hepatitis C,” Lindquist told the health board Tuesday.

“There’s not a single case of Ebola that got ignored, right? There is not a single case of measles in Clallam County that would get ignored.

“But you have hundreds of hepatitis C cases up here [being] ignored.”

Lindquist said he is “turning up the heat” on hepatitis C.

He received a grant from the Association of State Territorial Health Officials to prepare a statewide epidemiology profile to “really describe the burden of hepatitis,” he said.

An estimated 2.7 million to 3.5 million Americans have hepatitis C.

In Washington state, the number is somewhere between 54,000 and 70,000, Lindquist said.

Liver damage

If left untreated, hepatitis C can lead to liver cirrhosis, cancer and liver failure.

A person can have chronic hepatitis C for decades without even knowing it.

Most acute cases are not

recognized. Only a quarter of those with acute hepatitis C

have symptoms.

“They’re a lot like the flu, so during the flu season, a person with flu-like symptoms may have hepatitis C and you don’t even really know,” Lindquist said.

“About four out of five remain infected for the remainder of their life.”

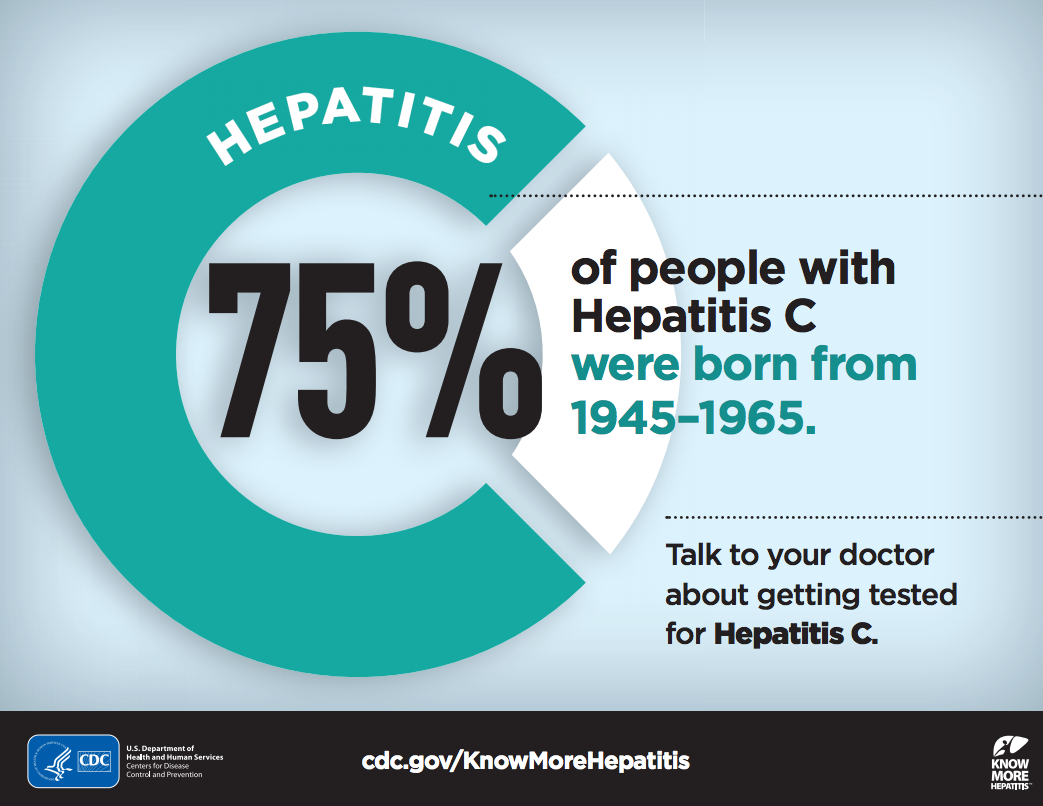

Baby boomers born between 1946 and 1966 account for most hepatitis C cases, Lindquist said.

Others at risk are those who have injected drugs, received blood before 1992, have been on long-term kidney dialysis, had abnormal liver tests or are HIV-infected.

In rare cases, hepatitis C can spread through medical and dental infections, sexual contact or through the shared use of personal items such as razors and piercing tools.

“But clearly,” Lindquist said, “injection drug use is the No. 1 [cause].”

“If you want to understand hepatitis C, you have to understand drug use,” he added.

“It’s that simple.”

New medications

The good news about hepatitis C is that new medications can cure it.

The bad news is that those drugs cost upward of $100,000 for a full regimen.

“The sad fact about this is that treatment can actually eradicate this virus,” Lindquist said.

“So that’s the dilemma. We’re not really testing for it. We’re not really reporting it. But we’ve got this lovely treatment that is really effective and that’s fairly new.”

Free hepatitis C screenings were offered by Peninsula College nursing students and staff and volunteers from Clallam County Health and Human Services and Volunteers in Medicine of the Olympics last Thursday in Port Angeles, Sequim and Forks.

Hepatitis C screenings are generally handled by primary care providers.

Denis Langlois, Jefferson Public Health nurse practitioner, said people born in the baby-boom era should be tested for hepatitis C.

While Jefferson County can no longer provide hepatitis C screenings, public health officials can help people sign up for insurance, Langlois said.

Volunteers in Medicine of the Olympics, or VIMO, recently began to offer hepatitis C services through a collaboration with the University of Washington, Executive Director Mary Hogan told the health board.

The UW’s Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project uses telecommunications and provides specialists to help screen, diagnose and treat hepatitis C patients in underserved areas.

“It really expands the options for treatment in Clallam County,” said Dr. Christopher Frank, Clallam County health officer.

The VIMO free clinic at 819 Georgiana St., in Port Angeles provides health care and dental care for those who can’t find it anywhere else.

One VIMO patient is now being treated for hepatitis C through the UW program.

“We’re hoping that we’ll continue to be successful in getting patients treated,” Hogan said.

“But it’s expensive,” she added, “and we take patients who don’t have insurance.”

Dr. Jeanette Stehr-Green, Clallam County Board of Health chairwoman, described the collaboration between VIMO and the UW as a “great resource for the whole community.”

“These are gastroenterologists and hepatologists who have incredible knowledge of this particular disease and give us cutting-edge information about how to treat it,” Stehr-Green said.

“For our free clinic to be the one dispensing this incredible knowledge and using it in our community is pretty impressive.”

Lindquist, former Kitsap County health officer and deputy Clallam County health officer, shared hepatitis C data from the Olympic Accountable Community of Health, or ACH, region.

The Olympic region covers Kitsap, Clallam and Jefferson counties.

“Basically, you are looking very similar to the U.S. and very similar to Washington state,” Lindquist said.

“So there’s no reason to think that you are protected or worse than [other regions]. That’s the way to look at it.”

The Olympic region has a population of about 359,000.

Between 233 and 349 cases of chronic hepatitis C were diagnosed in the Olympic region every year between 2010 and 2014.

There were 159 hepatitis C-related hospitalizations in the region during that time, costing $5.8 million.

“You could have bought treatment for all these people with that cost,” Lindquist said.

Hepatitis C was listed on 197 death certificates in the region between 2010 and 2014. The average age of death was 60.

“Clearly you decrease life expectancy with hepatitis C, and this is your data,” Lindquist said.

Hepatitis C epidemic

“There’s no question we’re in the midst of a hepatitis C epidemic. This is an epidemic in our backyard that is killing people.”

Hepatitis C statistics come from hospitalizations, cancer registries, death certificates and an electronic HIV surveillance system, among other sources.

“None of these data sources are perfect,” Lindquist said.

“They’re the best we have.”

Keys to hepatitis C intervention are identifying infection, education, linking patients to specialists and prevention, Lindquist said.

“I am not a hepatitis zealot,” Lindquist said.

“I am just an epidemiologist that looks at the data and says, ‘Here is something that we are obviously just absolutely missing.’ ”

________

Reporter Rob Ollikainen can be reached at 360-452-2345, ext. 56450, or at rollikainen@peninsuladailynews.com.