By Sandi Doughton

McClatchy News Service

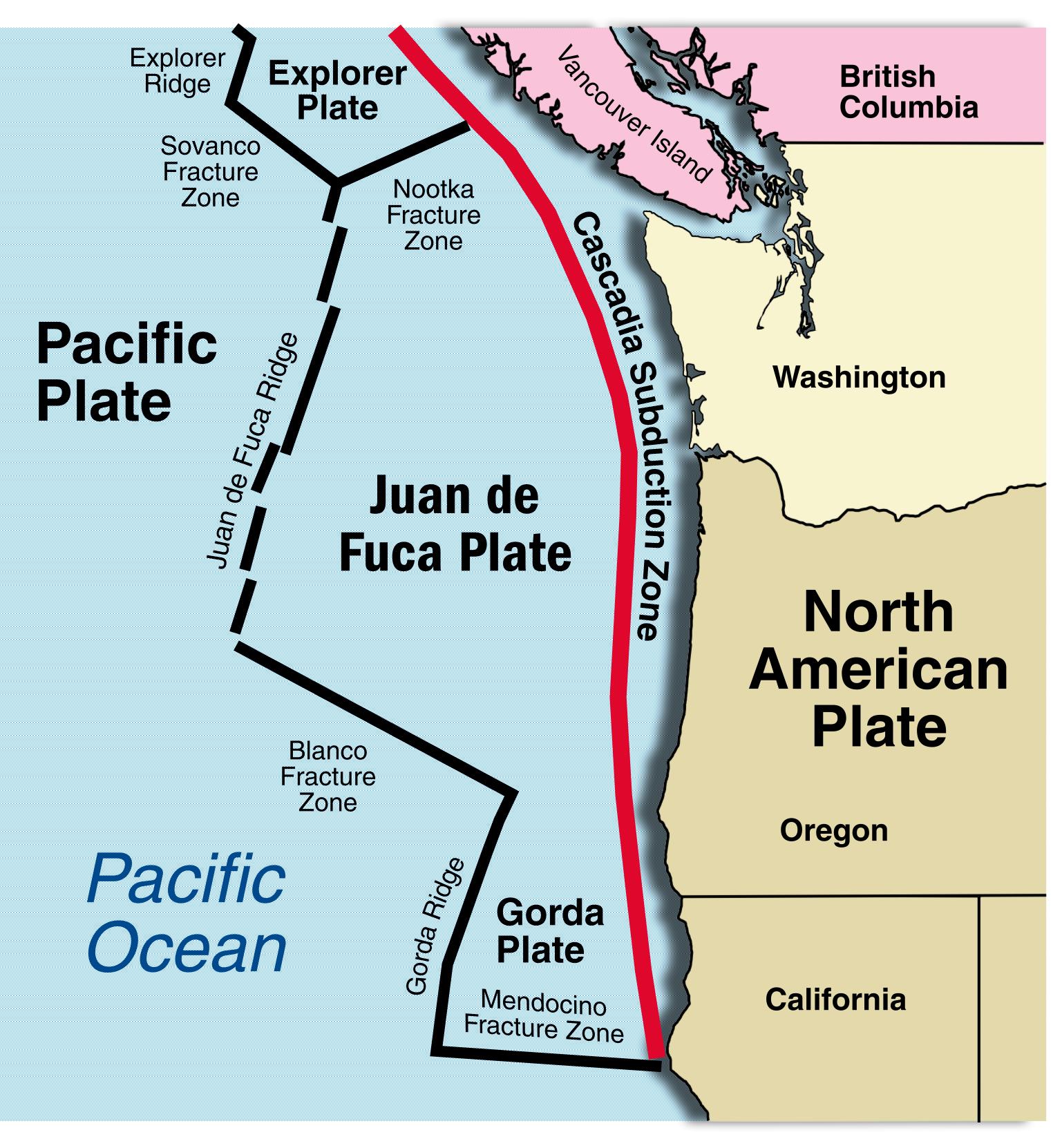

The Cascadia Subduction Zone hasn’t ripped in more than three centuries, so it’s surprising scientists know as much about it as they do.

On land, geologists have unearthed a 5,000-year record of megaquakes and tsunamis, based on the fact that the ground drops each time the 600-mile-long fault ruptures.

At sea, cores extracted from the ocean bottom have extended the record back 10,000 years based on mud layers, called turbidites, deposited by quake-triggered underwater landslides.

But a new analysis of cores collected more than four decades ago questions whether those landslide layers provide a reliable and comprehensive window into the region’s seismic past.

The debate is far from settled, but its outcome will be important for building codes and tsunami evacuation plans that factor in how frequently the region is rattled by megaquakes and just how powerful those quakes can be.

The most recent magnitude 9 Cascadia megaquake struck in the year 1700 — a date verified by tree-ring dating and historic accounts of the tsunami that crossed the Pacific and hit Japan.

The evidence on land suggests the entire Northwest coast gets slammed every 500 years on average — though the intervals between quakes have ranged from a few hundred to nearly a thousand years.

But evidence from seafloor cores suggests that the southern half of the fault — off the Oregon and Northern California coast — is much more dangerous, rupturing every 250 years.

The new analysis, published this month in the journal Geology, casts doubt on that interpretation, said lead author Brian Atwater, of the U.S. Geological Survey in Seattle.

“We’re not saying there’s no hazard or that the fault doesn’t make big earthquakes,” Atwater told The Seattle Times.

“Instead, we are asking what kind of earthquake history can you extract from deep sea turbidites?”

To answer that question, Atwater and his colleagues re-examined about three dozen cores pulled from the seafloor off Washington in the late 1960s — long before anyone realized it was a seismically active boundary between tectonic plates.

“Our research had nothing to do with earthquakes,” said Lehigh University professor Bobb Carson, who collected many of the cores when he was a graduate student at the University of Washington.

“It was simply trying to understand how sediments got from the continent out onto the deep seafloor.”

In 1990, John Adams of the Geological Survey of Canada was the first to re-examine some of the old cores and assert that the layers of silt and sand they contained were a record of giant landslides shaken loose by megaquakes.

Adams pointed out that cores from widely separated spots along the coast all contained the same number of landslide layers, which suggested the slides were triggered by quakes powerful enough to shake the entire region.

In recent years, Oregon State University researcher Chris Goldfinger has collected dozens of additional cores, which he says show evidence of 19 quakes of magnitude 9 or greater that ripped the entire length of the subduction zone in the past 10,000 years.

Goldfinger also argues that thinner layers in cores from the southern half of the fault show it generates earthquakes much more frequently.

But most of the old cores Atwater and his co-authors examined from off the northern coast of Washington contained few, if any, landslide layers.

The reason, the scientists say, is that there’s not much sediment piling up on the continental shelf in that area, compared with the amount dumped farther south by the Columbia River.

“If you’ve got a canyon that’s starved of sediment, you might shake it, but nothing happens,” Carson said.

That means the northern coast of Washington could have been shaken in the past by earthquakes that didn’t trigger any underwater landslides.

And if the number of landslide layers in the cores doesn’t provide a reliable quake record there, it raises questions about its reliability elsewhere — and whether the technique can distinguish between quakes that rupture the entire fault and those that rupture only a portion, Atwater said.

“If there’s a north-south difference in the frequency of turbidites, is it because of earthquakes, or is it because of sediment?” he asked.

Goldfinger said his faith in the turbidite record isn’t rattled.

The study of underwater landslides requires a detailed knowledge of bathymetry — the topography of the seafloor, he pointed out:

“You have to be very, very careful about your location, where you take your samples.”

Underwater landslides are channeled through a network of canyons on the continental shelf, so cores collected outside those active channels — including many in the new analysis — aren’t likely to contain turbidite layers.

“That is what you would expect,” Goldfinger said. “But when you look at cores from the active channel: Boom! You find a beautiful record.”

In the late 1960s, ships had only crude positioning systems, which makes it even harder to know exactly where the old cores were collected, he added.

The USGS recently boosted its estimates of earthquake risk in the Pacific Northwest, partly based on Goldfinger’s work suggesting more frequent quakes off Oregon and Northern California.

Some of those quakes have been corroborated by the discovery of tsunami sand layers in coastal lakes, and cores from inland lakes that show evidence of similar — though much smaller — earthquake-triggered slides, Goldfinger said.

About the only thing the two groups of scientists do agree on is the need for additional coring off the Northwest coast.

“There’s definitely a lot more to do,” Goldfinger said. “I’ve always felt our work is just a first pass at what you can do with paleoseismology.”