By John Kendall For Peninsula Daily News

EDITOR’S NOTE: Today is Port Angeles’ 150th birthday, based on President Abraham Lincoln’s June 19, 1862, signing of an executive order declaring the town site.

Port Angeles sesquicentennial events already have begun and will culminate with Heritage Days in September.

In commemoration of the sesquicentennial, the Peninsula Daily News has published a three-part series detailing the antics of the town’s founder, Victor Smith, and the Port Angeles’ dubious status as “second national city” in today’s final installment.

The series was researched and written by John Kendall, a former PDN copy editor who wrote a historical series on the Elwha River dams coinciding with the beginning of their removal last fall.

Parts 1 and 2 focused on Victor Smith, the town father whose clouded activities as customs collector made him reviled in Port Townsend but powerful enough to meet with President Lincoln, himself, in Washington, D.C. They can be accessed from the home page.

Today’s finale focuses on the “second national city” designation of Port Angeles.

The first national city? Washington, D.C. — that’s easy.

The second national city? Port Angeles — that’s complicated and based on misunderstandings.

The late June Robinson was a prolific Sequim historian and Peninsula Daily News history columnist who went to the sources for her research.

In 2002, she wrote:

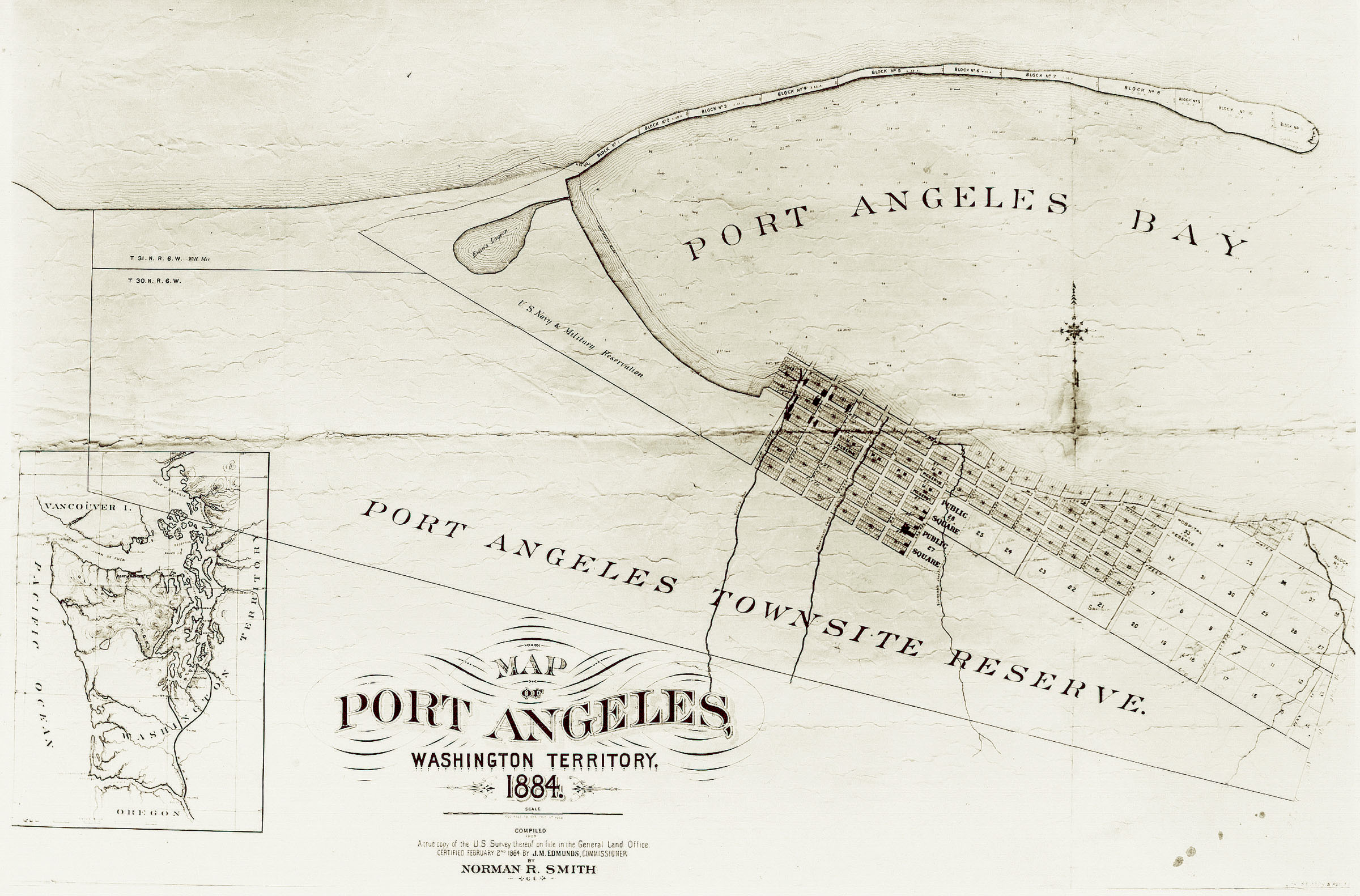

“[Abraham] Lincoln established a military and naval reserve in Port Angeles and Ediz Hook on June 19, 1862, meaning that the land was owned by the federal government and could not be sold or settled.

“The words ‘second national city’ were never coined by Lincoln in anything he said or wrote.

“Congress revoked the military and naval reserve status of Port Angeles and other cities across the United States in March 1863.

“The land south of Fourth Street was returned to reserve status from 1863 to 1890, but then Port Angeles residents convinced Congress to again reopen the land for settlement.

“But also in 1890, on the basis of the military reserve designation, the term ‘second national city’ was coined by the Port Angeles Board of Trade. It was an inducement to attract settlers.

“At least nine other townsites in Western Washington contained similar federal military reserves at one time or another. Port Angeles’ was the largest.”

And, no, the “second national city” status did not mean that a remote outpost in a remote corner of a remote territory was literally the second U.S. capital — a fallback capital if, during the Civil War, Confederate forces ever got close enough to Washington, D.C., to force a Union retreat to Port Angeles.

When the port of entry was moved from Port Angeles to Port Angeles in 1862, the community’s hub was the Customs House, marine hospital and wharf at the mouth of what is now Valley Creek.

Vessels stayed in the harbor only long enough to complete their business at the Customs House, a newspaper noted.

Once the reserve was established, no one could profit from land sale within the reserve.

The boundaries were the shoreline on the north, including Ediz Hook, Ennis Creek on the east, what is now Ocean View Cemetery on the west and what is now Lauridsen Boulevard on the south.

On March 3, 1863, the law now allowed the government to sell land to raise money to fight the Civil War.

Before any sales, such land had to be surveyed.

In Port Angeles, the map was approved in November 1863.

On May 4, 1864, 30 sales were recorded yielding $4,570.25 – not enough to cover survey costs.

The underwhelming response continued until the land rush of 1890.

A widespread, dependable marine transit system and a railroad had not yet reached the region.

But what had reached the remote region during the Civil War was fear — that Britain, controlling Vancouver Island, might attack along the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

There also were fears that Confederate privateers — pirate ships flying the rebel flag — might attack other vessels at sea or at remote port such as Neah Bay.

Local histories do not mention these factors, but it is plausible that then-Port Townsend customs collector Victor Smith, President Lincoln or the War Department had these fears in mind when the military and naval reserve was created specifically for Port Angeles on June 19, 1862 — exactly 150 years ago today.

Was it a warning — however hollow — to British naval forces at Esquimalt on Vancouver Island?

Victorian Britain’s siding with the Union was never a sure thing during the early days of the Civil War. Official British policy was to remain neutral.

But that was not Gov. James Douglas’ style.

As the lead official on Vancouver Island and Queen Victoria’s representative, he already had worried about thousands of Americans coming through the port of entry at Victoria on their way to goldfields beginning in 1858.

Douglas maintained order during the gold rush and asked the British Colonial Office to provide more assistance. Two warships and troops responded.

In 1859, an American farmer shot and killed a British farmer’s pig on the jointly occupied San Juan Island.

Successful diplomacy meant that the pig was the only casualty. International boundaries were established there in 1872.

Douglas wrote his superiors that since the U.S. had no defenses in Puget Sound, the Royal Navy “might occupy Puget Sound without molestation.”

Why not send two regiments of troops?

He argued: “There is no reason why we should not push overland from Puget Sound and establish advance posts on the Columbia River, maintaining it as a permanent frontier.”

Nothing came of it.

The British on Vancouver Island were figuratively rattling their sabers to scare off any feared American threat, while some Olympic Peninsula residents, like Smith, feared a British invasion.

But capturing the sidewheel cutter Shubrick — the marine mainstay of Smith’s customs operation — would be a definite blow to U.S. morale and commerce along the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

The incident “became the subject of a plot that was reported in so many versions that the truth has been obscured,” wrote one historian.

Around 1863, Confederate agents might have waited until the Shubrick was in Victoria, when they would overpower the crew and convert the U.S. vessel to a Confederate privateer.

In the memoirs of Victor Smith’s son, Norman, if the Shubrick became a privateer, it would allow “the Confederate government to complete devastation of our whaling fleet, then partially destroyed by the Shenandoah,” the deadly privateer that stalked the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans and the Yankee whaling fleet in the Bering Sea.

Whatever happened or didn’t, the Shubrick never became a privateer.

After the Civil War, fears quieted down.

Port Angeles became “The Gate City,” The Gateway City” or “Jewel in the Olympics.”

In 1924, the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated a stone marker now on the front lawn of the Museum at the Carnegie, 207 S. Lincoln St.

The inscription honors Lincoln ordering the reservation, which resulted in “making Port Angeles the Second National City.”

That seems to be the only official recognition of that designation Port Angeles today.